Summary

Over the past 7-8 years or so, there has been an interesting project taking place around Flanders Moss in west Stirlingshire to reduce deer damage to agriculture and the natural heritage. Although there isn’t a woodland angle as such in terms of objectives, trees have driven the situation to a very large extent, and the dynamic created has produced huge swathes of native woodland regeneration which are actually a real problem for all concerned. The following article sets out the context and past history. It takes some time to get to the tree bit, but the little tree twist at the end is interesting and will resonate with others elsewhere in Scotland.

Victor Clements, Chair of the Flanders Moss Deer Management Forum and native woodland advisor writes:

Introduction

Flanders Moss lies on the western part of the Carse of Stirling. It is a raised bog sitting on an otherwise flat landscape and is perhaps the best known and important lowland bog habitat in the country, being designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and also as a National Nature Reserve (NNR). NatureScot (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage) owns a relatively small part of the moss, with the majority of the area being owned by the surrounding farms and one sizeable estate.

The surrounding farmland is very fertile, and the area is well known for its ability to produce both livestock and crops. The upper River Forth winds its way through the area. Centuries ago, much of the area was covered in deep peat, but it was “improved” by cutting the peat, taking it to the Forth by horse and cart, and effectively just floating it all away, revealing the mineral soil beneath. An astonishing effort, and unlikely to be approved off today. The result is a very flat, fertile landscape, in which drainage is very important, supporting a large number of relatively small farms, the majority of whom are owner occupiers. Flanders Moss itself sits as a low, flat dome, slightly above this landscape. In many ways, it is counter-intuitive that the higher area should be wetter than the lower surrounding land, but this is the reality, and it has implications for the issues now at hand.

Most people drive by the area on the Stirling – Drymen – Glasgow road and never pay much attention to it, but NatureScot maintains an observation tower, a short circular walkway through some nice bog habitat and provides opportunities for education and conservation work parties on their reserve. This is well worth a visit and is easily accessed just off the road running north from Kippen to Thornhill. It is a great place for a short walk, full of interest, and accessible to all.

Red deer

About 20 – 25 years ago, red deer started to appear in the area, having never been seen there before. Most people agree that they appeared from the surrounding afforested landscape. In small numbers, they were a curiosity and generally welcomed by those who knew about them, but most people will have been unaware that they were there. The area contains a lot of woodland and other concealing habitats. While most farms in the area had some-one who might come in to shoot foxes/ rabbits/crows/geese and maybe the odd roe deer, dealing with the much larger red deer was a different matter, and numbers started to increase, mostly unnoticed.

About 10 years ago, numbers were such that they were beginning to cause problems for some people, but others also took advantage of them, for both venison and sporting reasons. The damage soon came to outweigh the benefits. As landowners on Flanders Moss with a regulatory role on the wider NNR, Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) staff began to take the brunt of the complaints. Meetings organized in Thornhill attracted sizeable crowds of angry farmers. SNH organized and chaired these but it was difficult because they were getting blamed. Someone had to be responsible, and SNH initially became the obvious target, although it was little to do with their site management staff.

A deer management plan was commissioned, which was unusual at the time in a lowland context. With little count or cull information available, and with few people with a positive interest in the animals, the initial plan concentrated on trying to analyse and understand what was going on.

The problem

In terms of the damage that was taking place, there were three concerns:

- Agricultural damage was creating the greatest agitation. Several farmers were no longer able to grow crops, with oats in particular being exceptionally vulnerable to red deer in the late summer months, but grass was getting impacted as well, and with the deer in large groups moving around the landscape, trampling damage was every bit as important as what they actually ate. They damaged fences and caused erosion along the River Forth at regular crossing places.

- The designated habitats were getting badly tracked, with bare peat doubling in extent by 2016. So, there was this wider public interest concern to nationally and internationally protected habitats.

- There was a suggestion from Police Scotland that accidents or near accidents on roads were increasing, especially around Aberfoyle. This was a particular problem as the deer themselves were very big, much larger than red deer in an open hill situation. A collision with one could easily be fatal, particularly if it was to happen on the main A811 Stirling- Glasgow road, which is quite fast, and a large deer would be the last thing that most people would expect to see.

However, it was the agricultural damage that was driving things. It is important to note that this is not just the type of damage that is a bit of an irritation. Several people had to stop growing crops completely, and then had the expense of having to buy in cereals for their winter feeding. One farmer estimated his annual costs at £2,000, another at £5,000. One was losing 20 – 30 acres of silage a year, another estimated that deer grazing his grass was delaying him putting out his cattle in the spring by a month. Another was cutting and baling his crops as arable silage, rather than risk them growing on and being ruined by deer, which could sometimes happen almost overnight if sizeable numbers came in. One small farmer had deer coming in to his yard to eat hay directly out of his barn, so bold had they become.

You might wonder how this was allowed to happen, but in addressing the situation, we first had to consider at what scale the problem should best be tackled.

The Flanders Moss Deer Management Forum area

In looking at the problem, it was important to define the area where action might be required. The area around Flanders Moss itself was fairly small, perhaps around 1500 ha, and this was unlikely to be big enough to address things. Arguably, the deer had come from the wider wooded area, which stretched up to Loch Venachar to the north, and Loch Lomond to the west, an area with a high proportion of conifers and other woodlands, a lot of deer, and sitting outside any deer management group. However, that area was huge, and the issues specific to Flanders Moss would almost certainly get lost at that level.

Discussions with farmers revealed similar problems with deer immediately to the west, which contained a similar mixture of farms, raised bogs and wooded areas.

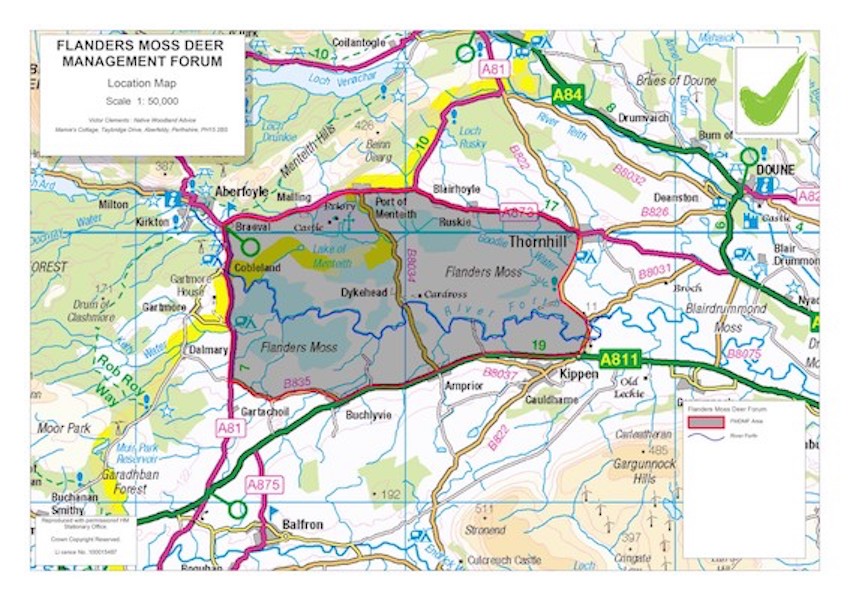

So, the Flanders Moss Deer Management Forum area was defined to include this area, which can be noted in Map 1. The area is approximately seven miles by four miles and is about 8,000 ha in total. The boundary is porous and defined by roads. Thornhill, Kippen, Arnprior, Buchlyvie, Aberfoyle and Port of Menteith all lie around the periphery of the area.

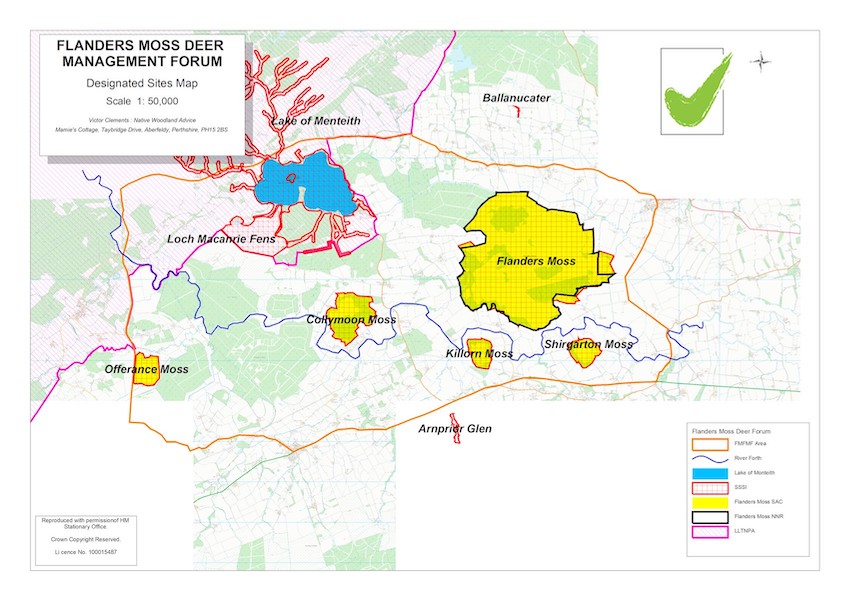

Of the 8,000 ha, about 300 ha is occupied by the Lake of Menteith, with just over 1,000 ha of woodland owned and managed by Forestry & Land Scotland (FLS), and an additional 1,000 ha of woodland in private ownership. In addition to Flanders Moss, there are additional designated raised bogs at Shigarton, Killorn, Collymoon and Offerance. Together, the “mosses” occupy another 1,000 ha. You can see these areas on the designated sites map below.

Being raised above the surrounding landscape, with deep vegetation and scattered trees as well as being very wet, these areas are extremely difficult to stalk due to the ground conditions, but also because people are effectively stalking on a dome, with flat land all around, so it can be extremely difficult to find a safe back stop when shooting. Combined with significant areas of rough grazing which includes tracts of gorse, scrub willow and rushes, about half of the Forum area is comprised of concealing habitats of one sort or another, a large proportion of which is difficult if not impossible to stalk. This is one part of the equation. There are plenty of places to hide. Agricultural land makes up the other 50 percent. The mixture is very intimate, with raised bog or trees close to most properties.

The other main part of the equation is the ownership structure. In addition to FLS, above, there is one sizeable private estate that has a number of tenant farmers, and three smaller estates/farms between 350 – 500 ha. But there are an additional thirty-one other farms as well, all owner occupiers. Four of these are 26 – 50 ha, nine are 51 – 75 ha, eleven are 76 -100 ha, four are 101 – 150 ha and three are 151 – 200 ha. So, there are a lot of small farms, almost all of whom have their own shooting provision.

A deer group in the area would have potentially 35 – 40 members, of which only 2 – 3 could take much value from the animals. Most would rather they were simply not there. Making such a group work is not easy.

Deer movements

Before the forum had come in to being in 2017, red deer had become well established in the area. They tended to lie up in inaccessible sanctuary areas during the day and go marauding on to fields at night. Because farmers had been shooting at them on a regular basis, the deer had learned to move in sizeable groups, often 30 – 40 animals, but sometimes up to a hundred. They were easily spooked by lights or shots and could move very quickly from one farm to another.

You can see a typical group of deer in the photo above of about thirty animals. They look odd in this landscape, but they are obviously moving with intent, with an experienced lead hind in charge. The photo below of the same group of animals, illustrates an important point. If that fence is an ownership boundary, then some-one can shoot the deer on one side, but not the other. The fence will not stop the deer. The many ownership boundaries associated with the small farms get in the way of effective control. You can try to co-ordinate efforts, but the deer move quickly from A to B to C and back again, and when the deer start to run, you cannot shoot safely without risking wounding them. Vigilant animals in big groups are a problem in any landscape, but more so in an area of small farms where the crops are valuable but very vulnerable. The deer behaviour was learned, and deeply ingrained. It was going to be important to try and break this down.

The problem at this point was that while there were many people who were capable of shooting a few deer, there were not enough shooting the numbers that were required to reduce the population. The fertility rate was extremely high, with almost every hind older than one year having a calf each year, and mortality would have been low.

What to do?

By 2018, some of the farmers had picked up a rumour that SNH was thinking of using their statutory powers of intervention. In most cases in Scotland, intervention would be resisted and avoided at all costs by landowners, but we had a very good discussion in Port of Menteith village hall about what it was that SNH could potentially do. The farmers present asked SNH to develop a package of measures that they could use to help. These were discussed and developed over six months or so in time for the next forum meeting. SNH had been given instruction to intervene.

What was being proposed was the use of Section 10 powers under the Deer (Scotland) Act of 1996. This allowed SNH to authorise permitted personnel to follow and kill deer on adjacent ground. There were many areas where the owner found it difficult to access, but where an adjacent owner could get into more easily. Several farmers had the frustrating experience in the past of deer jumping out of their fields and standing defiant in the bog outside their boundaries, knowing they were safe. The Section 10 authorisation allowed people to cross boundaries and close down these little sanctuaries. It was light touch and consensual, and never implemented in a hostile manner. People recognised the problem and tried to make a solution work. In addition to this ability to now cross boundaries to follow deer, SNH staff put in a lot of time co-ordinating efforts on the ground, providing advice and additional authorisations, and keeping track of who was doing what. They paid for the forum to be chaired and administered.

In addition, FLS played an important role. FLS had been restoring conifer plantations to bog habitat, but ground conditions where extremely difficult for deer control. On adjacent ground, farmers had fields where deer could be more easily controlled, but they often lacked the capacity to really go after numbers. Contracts were drawn up that allowed FLS contractors to shoot on adjacent fields. Sometimes, access to farmland allowed them to approach deer in the woodland/ bog areas, sometimes they were able to use these areas to approach deer in the fields. No money exchanged hands. Only a few people participated, we would have preferred to have seen more, but this flexibility helped and accounted for significant numbers. The advantage of using FLS was that they were not constrained by larder capacity. Some others were limited by the size of their own freezer in what they could shoot, and by what their friends might take. This was not the case now.

A number of recreational stalkers attended meetings, and it became clear that they too were capable of contributing to overall numbers.

Bigger numbers

Prior to SNH intervention, there were 283 red deer culled within the area in 2017 – 2018.

In 2018 – 19, this rose to 519, which included some animals just outwith the forum boundary. The Stirling Observer screamed “Deer Cull on the Carse” on its front page, “500 animals targeted this year”. The Times did a piece on it, and even gave it an Editorial. BBC Radio Four did a piece speaking to local farmers. In general, people understood the rationale. There was no controversy, although it was difficult to understand how so many animals could be present in such a small area.

We now know of course that there are many areas in Scotland where big numbers of deer are having to be culled in similar situations, at the intersection of forestry, farmland and open hill. We have it in Perthshire, in coastal Aberdeenshire, in Donside, and many other areas which never have had red deer before.

The following years brought additional culls of 376, 344, 423 and 254 animals, or 1916 in total, an average of 383 red deer a year, or an average annual cull of 5 red deer per sq km in a lowland area.

Over the same period, SNH carried out a number of thermal imaging counts to try and get a handle on the population, aided in recent years by drone counting. These counts were usually carried out in April/ May, but sometimes in late autumn as well. Count totals were 427, 439, 305, 318, 459, 385, 292 & 350, or an average of 371 animals per count.

You will note that the average number culled was higher than the number counted, so either some animals were always hidden, or there was movement in to the area from adjacent ground, or probably a combination of both. If people thought they were removing them all, they weren’t.

An improving situation

Over the past two years or so, many farmers have reported an improving situation, with less reports of damage, and most people have considered this to be a successful operation.

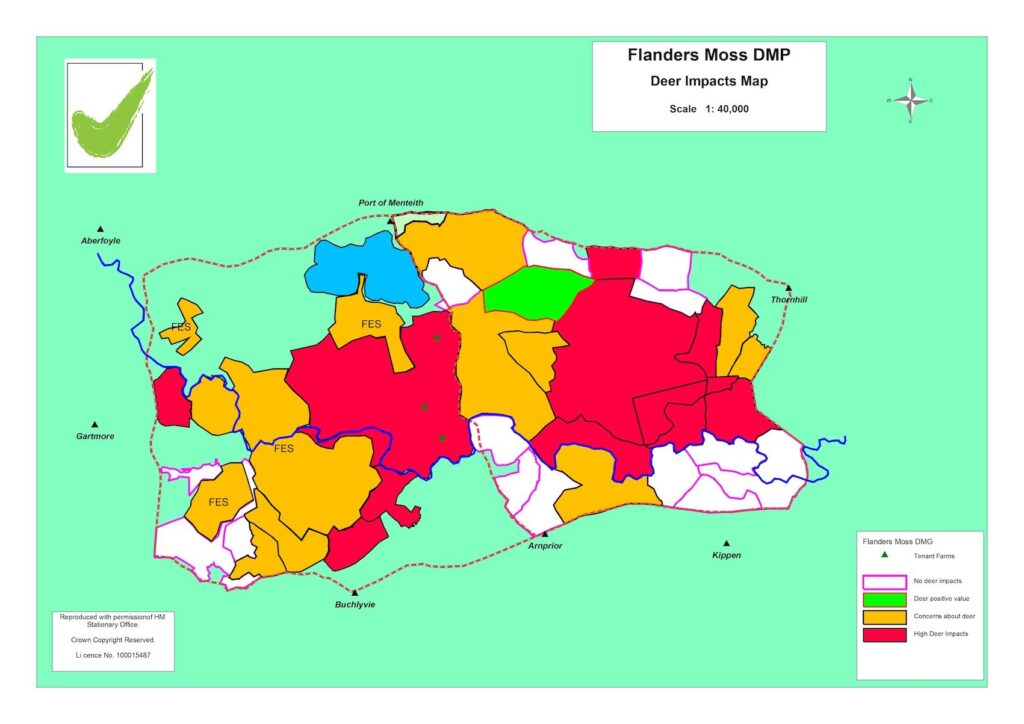

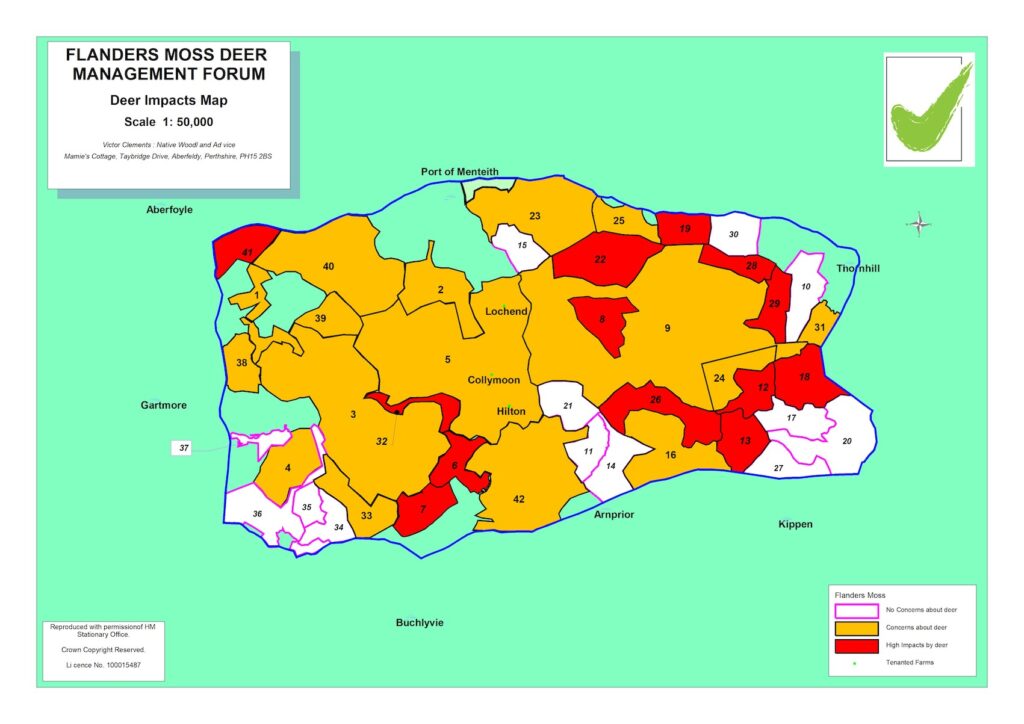

On the maps below (maps 3 and 4) the green colour is anyone happy with the deer numbers, the amber is people with concerns, the red is people with serious problems, and the white is people who are largely unaffected. The maps show that over the period 2017 – 21 that (1) More people are now engaged and providing information and feedback, and (2) a lot of the red has turned to amber, so while the problem has not gone away, the worst of the really bad impacts have reduced. Done today, the red would have contracted further. Obviously, there are mixed objectives on some properties, and the approach to deer may be different, depending on who you speak to, but the colours presented here give a broad indication of the direction of travel over five years or so.

SNH had done a good job and was now trying to wind down its operations to move on to other projects, but maintaining a lighter touch approach, and maintaining communications. The operation had been time consuming and costly in terms of staff hours, but the effort had been considered a success.

However, counts have stayed more or less the same, and culls remain high. Two good summers allowed farmers to get their crops and grass off quickly, and that will have reduced deer damage. Some of those reporting less damage do not now have the crops that they damaged before. In May 2023, we had two farmers come to tell of problems again, so this is not going away, and the effort has to be maintained.

Trees

So, where do trees come in to all of this?

There is no doubt that the deer came from the wider afforested area, perhaps when deer fences started to break down, or when harvesting operations caused deer to disperse.

The mixture of trees and raised bogs covering up to half of the area provided the concealing habitat that disguised the presence of so many numbers for so long, and then made it very difficult to effectively control them. Trees increase the holding capacity for deer in any landscape. We see that elsewhere in Scotland as well.

But there is also a sting in the tail that the deer have created at Flanders. The daily movements of hundreds of animals back and forwards to different fields has very effectively scarified the bog surfaces and provided the perfect situations for establishment of birch trees in particular. There has always been some of this around Flanders, but the pace of growth is accelerating very quickly now. Back in 2016, there was a little bit of a conspiracy theory going around suggesting that SNH wanted deer to keep the birch regeneration in check, but the more perceptive farmers noted the opposite was true. The deer were not interested in downy birch growing on a nutrient poor substrate when they had grass and crops all around them.

They simply walked by the trees to get to the fields, but every step they took on the wet surface created another regeneration niche.

To reinforce the point, most deer impacts recorded in the Native Woods of Scotland Survey (NWSS) showed low and medium impacts, not the high ones you might expect with so many deer around. You can even see oak regeneration coming away within a sea of downy birch. The seedling densities will range from a few hundred to 30,000 – 50,000 per ha and will be 100,000+ per ha in some local areas.

Now, all five of the raised bog areas have this expanding birch regeneration. It is not the tracking which will lead to unfavourable status, but the new woodland it is creating. It is very difficult to stop. Indeed, it is inevitable that this will get away, and this is a big threat to the bog habitat.

In the west, the FLS woodlands that were felled and restored to bog are not looking much like bog either at the moment. In addition to the deer scarifying the surface, brash from the previous crop of trees is providing plenty of nutrients for a new generation, a mixture of birch, willow and conifer regeneration, principally sitka spruce and lodgepole pine. The colour of these trees and the annual height increment shows they are in good health. Amongst all this too is a healthy proportion of oak trees. We will see how far they get trying to grow on peat, but at the moment, they are looking good. Surprisingly, aspen is locally abundant in the regeneration, but the source of this is not known. There are few obvious mature trees around. Willow is very well represented. To a woodland advisor, the intimate mixture of conifers and native broadleaves of varied species is a delight, all happening without any cost. Something you could not design better if you tried.

But here is the problem. There are areas in Scotland where we want to get native woodland regeneration and struggle to do this because of high deer numbers, such as at some nearby SSSI sites. In the Flanders Deer Management Forum area, high deer numbers are causing native woodland regeneration in areas where we do not want it. FLS and NatureScot want to stop it, but there is possibly 1,000 hectares of it now in total, and there will be more as well as other areas are felled in the near future. In the battle between trees and bog, it is the trees that look like winning in the end.

If we value our bogs for CO2 sequestration, that is a problem. It will also increase the deer holding capacity of the area, throwing more pressure on to the farmland in future, so control efforts will need to evolve and become smarter and more co-ordinated.

The ghosts in the pictures above that wander Flanders Moss at night are therefore changing the landscape, but not in the way we might expect, and certainly not in the way that we might want. They are going to give us some wonderful woodlands, full of diversity and interest. We can reduce their numbers, but can we turn back what they have left us as a legacy, and do we actually want to do that?

The interaction between deer, farmers, bogs and trees at Flanders is interesting and complicated, and gives us all something that we can learn from as we try and plan for the future in a world where food security and CO2 sequestration are hugely important. We may have to redefine what is natural and what is not. In this case, nature appears to be working against us. Is it right and does nature know something that we do not, or are we right, and this is a situation which we can yet manage? I think we would all like to know the answer to that question.

Lessons learned

The Flanders experience shows that problems can be overcome, and authorisations and interventions used to support people who have bought in to a plan. To drive down a deer population, you really do have to go after the numbers with sustained pressure, and you need capacity to do that. You do need to collaborate, and you do need to break down ownership boundaries if you have a lot of smaller landholdings. Having fewer people each shooting more deer is much more effective than many people shooting one or two each. Lardering capacity is important.

The FLS arrangement was hugely important, but it was frustrating too. There were four different stalking/ contractor arrangements over the period, some of which worked and some of which did not. Their tendering requirements proved to be very disruptive. When working with farmers, the relationships are important. When you have someone good who they trust, you have to work with them and try to retain them. Chopping and changing is not good.

Going forwards however, the most important consideration will still be how to make a deer group work in a lowland situation. When there was a problem, farmers came to the meetings. When the problem seemed to be disappearing, they stayed away. SNH/NatureScot covered the cost of chairing and administering the forum. Despite many attempts to do so, it has not been possible to recruit a Chair from among the forum membership, so an external chair paid by NatureScot is still required. Most deer groups in Scotland enjoy good participation because the people involved have a shared interest in deer. How can you operate a group forum when almost all the potential members don’t want to see any deer at all? How can that be made sustainable? One thing we have tried to do is to make the deer forum into more of a wildlife forum. There are large numbers of geese grazing within the area, which some say eat more grass and crops than the deer do. Beavers are now well established. It is a bit early yet, but maybe a forum could eventually enjoy more sustained support if there were a variety of wildlife issues which farmers felt they wanted to discuss, not just deer. Perhaps then the forum could sustain itself.

The Flanders experience will eventually be considered a success when the forum is properly sustainable, when the farmers and landowners take ownership of it, and when NatureScot attends by invitation only. It is not quite there yet, but there are a good group of people involved, and we will get there in the end.

You can find more information on the Flanders Moss Deer Management Forum here:

Information on the Flanders Moss National Nature Reserve can be found at this link:

Victor Clements is a native woodland advisor working in Highland Perthshire. He is Chair to the Flanders Moss Deer Management Forum, paid for by Nature Scot. The drone images in this article are supplied by and used with permission of BH Wildlife Consultancy.